Fighting against duplication

At large companies like Amazon, it’s inevitable that multiple independent teams will attempt to solve the same, or closely related, problems. One approach that optimizes for time-to-market is for each team to independently make decisions, build, and deliver solutions. At Amazon, this aligns with the “bias for action” leadership principle when a team needs to act swiftly:

Speed matters in business. Many decisions and actions are reversible and do not need extensive study. We value calculated risk taking.

While launching a solution rapidly is greatly desirable, we tend to underestimate the cost of duplication and its impact on sustained innovation.

Why does speed matter in business?

The need to launch. We build minimum viable products to validate our hypotheses about what customers want with real user data. Our aim is to learn as fast as possible what customers truly need while minimizing wasted engineering efforts.

All projects are vulnerable to unpredictable shocks, with their vulnerability growing as time passes. — Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner, How Big Things Get Done.

Delivering a project promptly also shields it from “black swan” events. For example, within a large company, a reorganization or sudden budget cuts could easily switch ownership or halt an undelivered project altogether.

The need for sustained launches. What we really want is for speed to be viewed as a “feature” by our customers. They need to know that our solutions are not only reliable but will also improve faster than anyone else’s.

[…] go out there and have huge dreams, then show up to work the next morning and relentlessly incrementally achieve them. — Luiz André Barroso, The Roofshot Manifesto.

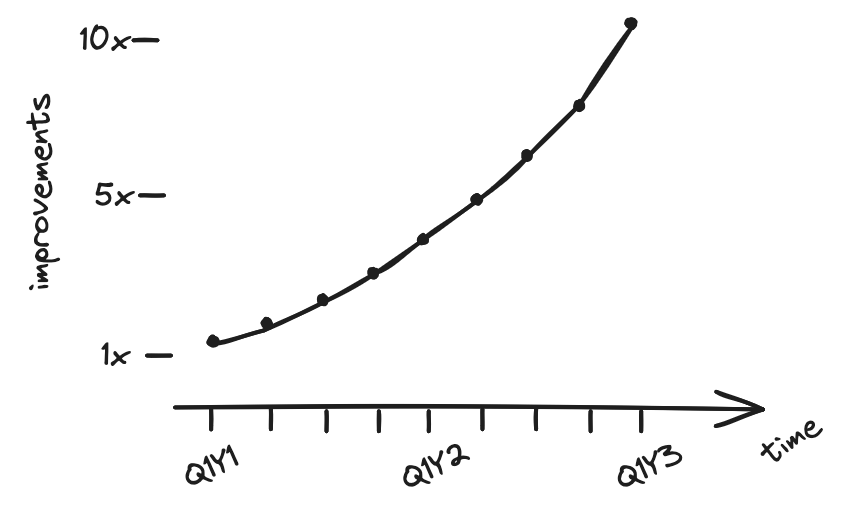

Imagine we can improve our product by 30% every quarter, then in 2 ¼ years we would achieve over 10x improvement. Additionally, our customers would receive these improvements gradually instead of waiting two years for a potential step function leap.

Imagine we can improve our product by 30% every quarter, then in 2 ¼ years we would achieve over 10x improvement. Additionally, our customers would receive these improvements gradually instead of waiting two years for a potential step function leap.

What is the cost of duplication?

While duplication across teams accelerates initial launches, it impairs the delivery of sustained launches.

Inefficiency. Imagine an organization with three different 4-person teams all working on the same or related problems. We’re missing the opportunity to allocate two of these teams (8 people) to solve distinct problems and deliver new user experiences for our customers. Ensuring that problems are divided & conquered independently is a surefire way of working faster.

Deprecations are inevitable.

Even at huge profitable companies, in some corners you’ll occasionally find an understaffed project sliding deeper and deeper into tech debt. Users may still love it, and it may even be net profitable, but not profitable enough to pay for the additional engineering time to dig it out. Such a project is destined to die, and the only question is when. The answer is “whenever some executive finally notices.” — Avery Pennarun, Tech debt metaphor maximalism.

I’ve experienced two reorganizations characterized by similar patterns. Public-facing duplicated projects, even those with devoted customers, are inevitably reduced to operational maintenance if their profitability is only marginal. Resources from these less lucrative projects can be redirected to more profitable ones lacking the headcount to accelerate innovation or to finance new ambitious bets. Meanwhile, internal projects lacking external revenue are destined to merge as they merely incur costs for the organization.

Deprecations are hard. Let’s start by analyzing the cost of deprecating internal projects where owners have the affordance of modifying the client code.

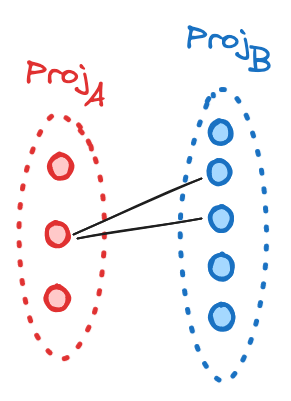

If the project we are converging to, say \(Proj_B\), already has overlapping functionality with the project we are deprecating, say \(Proj_A\), then the cost is approximately the sum of refactors across all client codebases to swap the dependency from \(Proj_A\) to \(Proj_B\). If clients did not isolate and wrap the \(Proj_A\) dependency in a separate module, then this refactor can be quite costly.

If the project we are converging to, say \(Proj_B\), already has overlapping functionality with the project we are deprecating, say \(Proj_A\), then the cost is approximately the sum of refactors across all client codebases to swap the dependency from \(Proj_A\) to \(Proj_B\). If clients did not isolate and wrap the \(Proj_A\) dependency in a separate module, then this refactor can be quite costly.

Unfortunately, the more realistic scenario is that these projects solve tangentially related, not identical, problems. Their feature sets will differ slightly, meaning \(Proj_A\)’s functionality may lack a mapping to \(Proj_B\).

Unfortunately, the more realistic scenario is that these projects solve tangentially related, not identical, problems. Their feature sets will differ slightly, meaning \(Proj_A\)’s functionality may lack a mapping to \(Proj_B\).

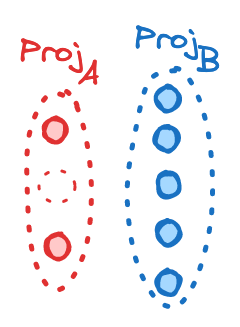

If the missing functionality will benefit many clients of \(Proj_B\), then we can consider adding it.

If the missing functionality will benefit many clients of \(Proj_B\), then we can consider adding it.

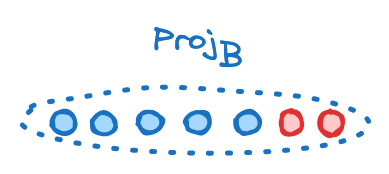

Alternatively, we can progressively refactor clients to use \(Proj_B\)’s overlapping functionality, then pivot \(Proj_A\) to support only the remaining niche use cases.

Alternatively, we can progressively refactor clients to use \(Proj_B\)’s overlapping functionality, then pivot \(Proj_A\) to support only the remaining niche use cases.

Finally, we can decide not to retrofit the missing functionality at all, burdening clients with filling the gap.

Whichever deprecation route we choose, in addition to client refactoring costs, someone must pay to close the gap between projects.

Lastly, deprecations are emotionally charged. Managers will lose impact and engineering teams must detach from beloved projects. Creating alignment on which project gets to survive, even with impartial usage data, is extremely unpleasant and time-consuming.

“Keep the lights on” wastes energy. For external projects where we cannot modify client code to swap dependencies, the common solution is a maintenance only mode. Sadly, these projects incur ongoing cost as they must address customer issues, update their codebases as bugs are discovered or as the environment around them evolves, and release changes via esoteric delivery pipelines. For example, if a library announces an end-of-support date with no further security patches, the project must update its codebase to the newer major version.

Duplication as debt. If we take the perspective of viewing project duplication as a form of technical debt, then the principal is “how many engineers solve similar problems” while the interest is “how many engineers it takes to deprecate duplicates or maintain them”.

Code is a liability, not an asset

[…] too often we choose to implement new ideas by designing a new thing from scratch, resulting in multiple systems solving similar problems. Besides this being inefficient, it also taxes our developers to navigate the resulting maze of options when trying to build new products, leading to decreased product innovation velocity. On the other hand, implementing a new idea in an existing system will almost always yield greater return on investment — Luiz André Barroso, Innovate Within.

On the other hand, simplicity takes work but it’s all up front. Simplicity is very hard to design, but it’s easier to build and much easier to maintain. By avoiding complexity, simplicity’s benefits are exponential. — Rob Pike, Simplicity.

It’s easy to start coding immediately on a project and claim territory within a large company. As builders, we must resist the urge to push more code and instead spend time seeking simplicity. We need to understand the duplication cost accurately. Can we build this component so that it doesn’t only solve the problems of our team but also for others? Did we seek diverse opinions during design? Can we make the project easy to decommission by providing a migration path to another solution? Can we have a larger impact by improving an existing solution rather than building a new competing product?