Goodput degradation in rate-limited systems

In this post, we’ll explore how “goodput” (the rate of useful, successful work completed) degrades under increasing load, particularly in multi-step workflows that depend on rate-limited services. We’ll also see why throttling incoming requests leads to more useful work.

To illustrate this observation, let’s imagine we have a worker service that polls messages from a queue and needs to call a single downstream dependency to process each message.

To illustrate this observation, let’s imagine we have a worker service that polls messages from a queue and needs to call a single downstream dependency to process each message.

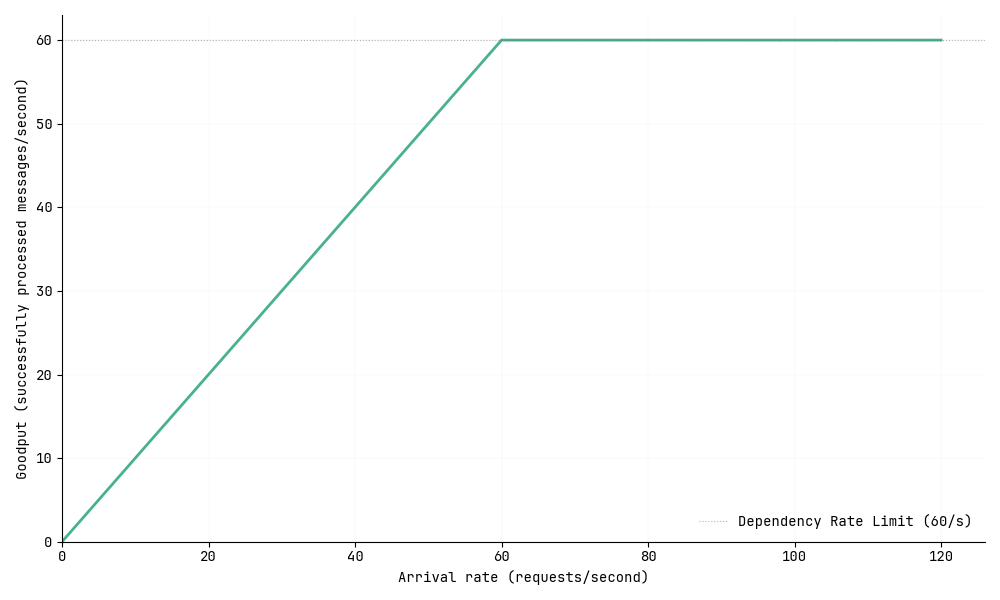

Single-call workflow performance

In this initial setup, we need just one successful call to the dependency to complete a unit of work. Our example dependency has a rate limit of 60 requests per second, but both our queue and worker service can scale elastically to handle incoming load.

When we plot the arrival rate of messages against goodput, the behavior is exactly what we’d expect. Goodput increases linearly with the arrival rate until we hit our dependency’s rate limit of 60 requests per second. After that point, it plateaus as additional requests simply fail.

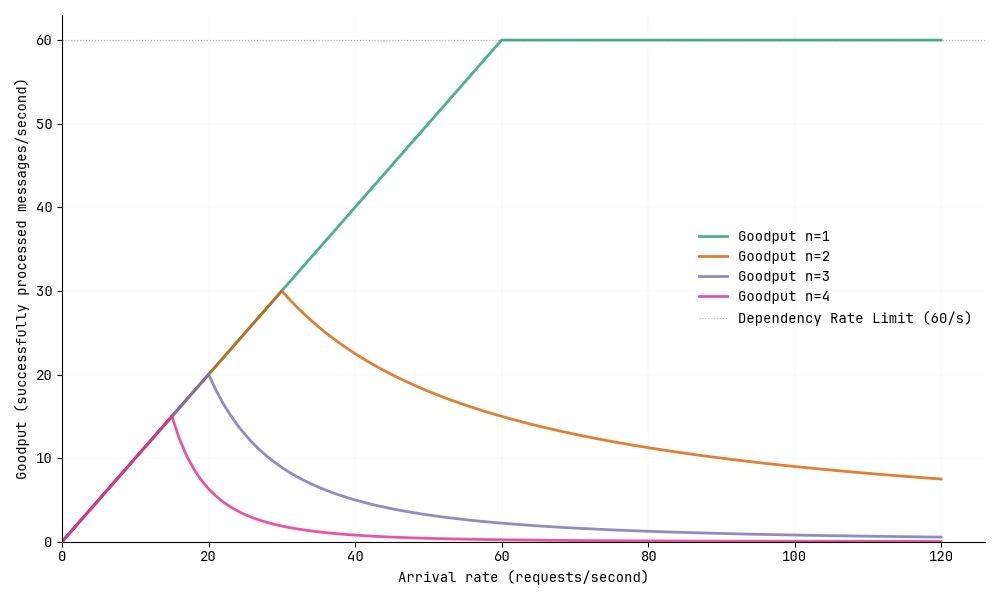

Multi-call parallel workflow performance

Now let’s modify our scenario. Instead of one call per message, imagine each message requires \(n\) successful calls to complete its work. We’ll further assume these calls are made in parallel and complete within a 1-second window.

The behavior changes dramatically. While we still see that initial linear increase in goodput, the system now peaks much earlier as expected — specifically at \(\frac{60}{n}\) rps.

The behavior changes dramatically. While we still see that initial linear increase in goodput, the system now peaks much earlier as expected — specifically at \(\frac{60}{n}\) rps.

After we exceed the rate limit, the goodput doesn’t plateau—it drops sharply!

We can model the probability of a single call to succeed beyond the peak as the \(capacity\) (60 requests/second) divided by the total number of calls we’re attempting (arrival rate \(\times n\)). For a message to process successfully, all \(n\) of its calls need to succeed. This means our success probability is \((\frac{capacity}{arrival\ rate \times n})^n\) for each message.

For instance, if we have three calls per message (\(n=3\)) and an arrival rate of 30 rps, the probability that all 3 calls succeed is \(\frac{60}{30\times3} \times \frac{60}{30\times3} \times \frac{60}{30\times3} \approx 0.3\). This means our goodput become \(30 \times 0.3 = 9\) requests per second.

That exponential factor \(n\) explains why the goodput drops so steeply once we exceed the rate limit.

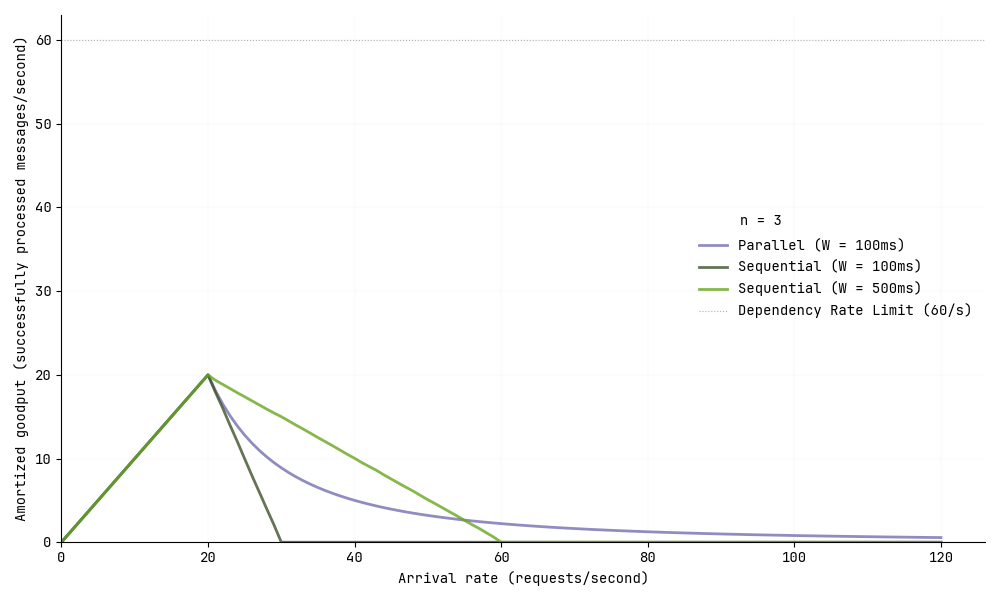

Multi-call sequential workflow performance

The call pattern for a workflow impacts the shape the curve. Consider the same scenario with three calls per message (\(n=3\)), but now the calls happen sequentially instead of in parallel. We’ll also consider \(W\), which represents the mean processing time of a single call.

While the goodput still increases linearly until reaching the peak of \(\frac{capacity}{n}\), the degradation beyond the peak follows a linear pattern rather than the curved exponential drop we saw with parallel calls. 1

Remedy

Our takeaway is that although intuitively one might expect for the goodput to plateau after a certain point, we instead observe that additional load results in a degradation of useful work regardless of the workflow call pattern.

Therefore, a simple remedy to make sure we do as much good work as possible is to throttle at the service entry point. For our simple setup where there’s a single dependency and calls complete in under one second, this throttle threshold turns out to be \(\frac{capacity}{n}\).

Naturally, setting up input throttling causes messages to pile up in the input queue since we cannot keep up with the arrival rate. This means we need a strategy for handling excess messages such as only processing a sample of messages.

Thanks to Mitchell Valine for highlighting this observation and the discussions on Slack!